The Expropriated Catullus: The Battle for Sirmione’s Roman Ruins

Nothing is conquered in life without great effort by mortals.” — Horace

Location: Sirmione | Era: 20th Century | Reading Time: 4 mins

The Lead: Today, the Grotte di Catullo is the jewel of Sirmione, a majestic archaeological park overlooking Lake Garda. However, its transition from private olive groves to a state-owned monument was far from peaceful. It was a decades-long saga of bureaucratic battles, local resistance, and debates over the true value of these “grand ruins.”

🗝️ Key Facts

- Where: Grotte di Catullo, Sirmione

- Era: 1911 – 1952

- Visitability: Open to the public (Archaeological Site)

A Ruin Among the Olives

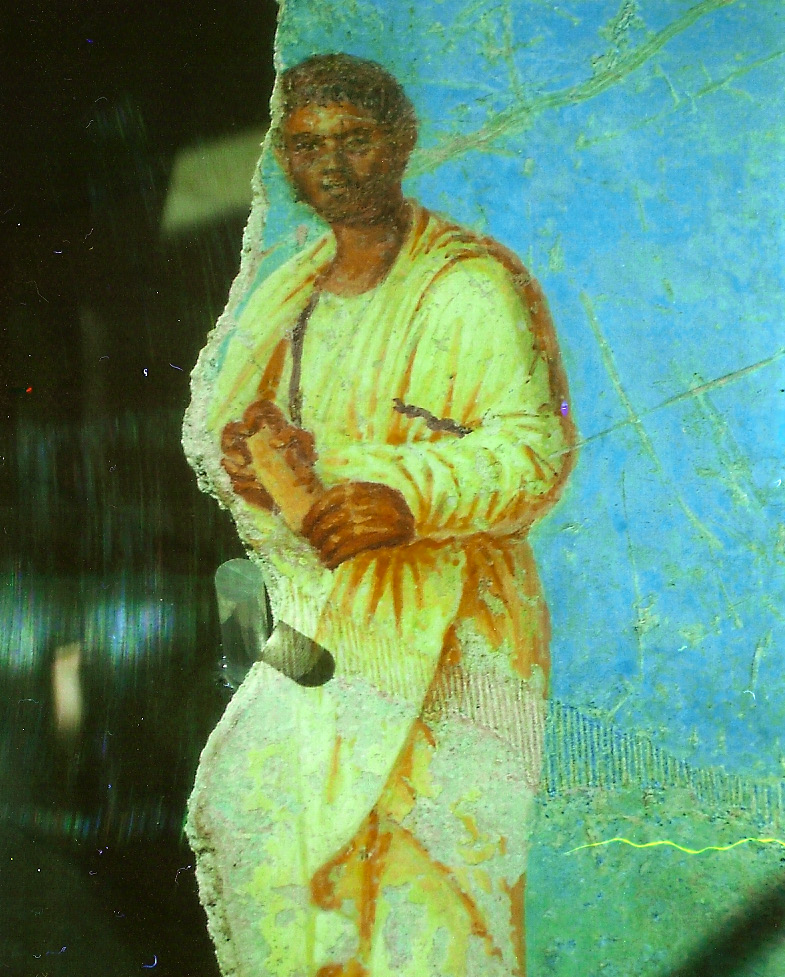

For centuries, the massive structure built in the first century AD lay in decay. By the 1830s, when the poet Arici visited, the area was a “sad ruin.” He described how time, storms, and human neglect had broken down what once stood high. For nearly two millennia, the site remained largely untouched, until the 20th century brought a new desire to reclaim the past.

Everything changed in 1911 when a law prohibited new construction in the area traditionally known as the “Grotte di Catullo,” a clear prelude to expropriation.

The Long Road to Expropriation

The process of turning private land into a public monument was slow and fraught with complications. In 1920, an initial agreement was made between the Superintendency of Monuments of Lombardy and a local landowner, Angelo Gennari, to sell nearly 9,000 square meters. However, this agreement lacked the necessary ministerial approval and stalled.

It wasn’t until the chaotic years of World War II that the state made its move. In 1942, the Municipality of Sirmione sought to acquire the archaeological zone based on the old agreements. By 1944, under the shadow of the Salò Republic, Minister Biggini decreed the “public utility” of the lands containing the “grand Roman ruins.”

This decree affected major local players, including the Società Anonima Terme e Grandi Alberghi (the hotel and thermal baths company) and the local Parish, setting the stage for a conflict between national heritage and local interests.

“Shapeless Cells” and Local Resistance

The expropriation did not sit well with the people of Sirmione. In 1945, Superintendent Nevio Degrassi pushed for the immediate acceptance of a low offer (6.25 Lira per square meter), arguing that the archaeological park would eventually boost tourism.

The locals disagreed. On February 20, 1946, a formal opposition was presented to the Prefect. The document, signed by prominent figures including the parish priest Don Giuseppe Martini, declared that “all of Sirmione is moved.” They rejected the Superintendent’s “splendid gift” to the nation, arguing that public interest should not violate individual rights.

In a scathing attack on the aesthetic value of the site, the opposing landowners described the ruins not as a majestic monument, but as “a complex of shapeless, monotonous, squalid cells; a gloomy invitation for hoopoes and bats.” They proposed restricting the archaeological zone to a minimum and freeing the surrounding lands for other uses.

The Parish and the Olive Trees

The conflict continued into the 1950s. In 1950, the new parish priest, Don Lino Zorzi, sent a vigorous protest to the Minister of Public Education. His concern was economic: the expropriation included the “Parish banks,” an olive grove of nearly 400 trees that provided the bulk of the parish’s income.

Don Zorzi calculated that the trees produced 540 kg of oil per harvest, valued at 270,000 Lire, yet the parish had received a total compensation of only 220,000 Lire. He argued for a compromise that would allow the church to continue cultivating the land, suggesting the meager compensation be treated as a partial payment for damages suffered during the war.

Skepticism Over Catullus

The tension culminated in 1952 when the Town Council passed a motion signed by 419 heads of families. The document was a direct challenge to the romanticized narrative of the site.

The locals asserted there was “no factual data” to prove the Roman poet Catullus ever had a villa there. They refused to classify the “remains of a purely grand Roman bathhouse” as a national monument. Furthermore, they argued that the ruins were only being valorized because of the existing thermal and hotel industry, not the other way around. They feared that introducing an entrance fee to the ruins would damage the local hotel economy, which had fought tenaciously for the town’s future.

Despite the warnings and the local skepticism about the future, the state prevailed. The “Grotte” were preserved, becoming the iconic landmark we see today, proving that sometimes, looking too closely at the “wrath of storms” and bureaucratic fights obscures the enduring legacy of history.